While I don't necessarily subscribe to the notion that testing in track and field is unhelpful, I have taken some time to reflect on its purpose during my tenure at MSU. Each fall, we schedule testing in weeks 4 and 8. As we conclude week 4, we possess an array of numerical data that provides insights into each athlete's performance. But what do we do next with this data? Is dedicating an entire week, even if it's a recovery week, to testing truly worth it? In this post, I will delve into the pros and cons of testing.

In our sport, there is a multitude of physical tests to administer, and below is the framework we adhere to during each testing block. We always conduct these tests indoors to mitigate the influence of weather conditions that could skew results.

Week 4 (2-3 reps of each test with 6-8 minutes between reps):

Monday: 30m from a 3-point start / standing long jump (SLJ).

Tuesday: 30m fly / standing triple jump (STJ).

Wednesday: Rep max in the weight room (typically involving back or front squat, clean, and bench).

Thursday: Overhead back and under forward shotput throws.

Friday: Optional workout (dependent on how the athlete is feeling).

Week 8 (2-3 reps of each test):

Monday: 30m fly.

Tuesday: Thrower’s pentathlon or LSU pentathlon (whichever terminology you prefer):

30m from a 3-point start, SLJ, STJ, OHB, UF, each performed 2-3 times with combined events-style scoring across all event groups (throwers substituting STJ with a 3-hop).

Wednesday: Rest day.

Thursday: 20-second run.

Friday: 45-second run.

Week 11 – No formal testing:

Intrasquad (FAT - Fully Automatic Timing):

Split into purple and gold teams based on testing depth charts.

All sprinters participate in a 60m dash and one additional event.

The 60m dash enables comparison to 60m projections from previous testing.

Team scores are recorded, providing a dress rehearsal for upcoming competitions.

So, what is the goal of these tests?

Inspired by Sahil Bloom, who discussed the "Writing Knife Block" concept (below), which encourages deep thinking on a topic, I have been using testing blocks in my fall training for 13 years. Over this time, I have created thoughtful presentations, delved into results, and explored methods to analyze the data. I have paired down my toolbox of tests to focus on answering a few fundamental questions: Can athletes accelerate? Can they sprint? Can they generate power? And when do they stop sprinting efficiently? The following are the tests that help provide answers to those questions:

30m from 3pt – Can you accelerate?

30m fly – Can you sprint?

Standing Long Jump – Can you produce power?

Standing Triple Jump – Can you produce power?

Overhead Back Shotput Throw – Can you produce power?

Under Forward Shotput Throw – Can you produce power?

20 second run – When do you stop sprinting efficiently?

45 second run – When do you stop sprinting efficiently?

These tests allow me to diagnose and gain clarity about our athletes, whether they are new to the program or in their fifth year. Each athlete has a unique equation for improvement, and testing provides the initial insights necessary to guide them in future training blocks. For instance, if an athlete excels in the 30m from a 3-point start and the 30m fly but struggles in the 20-second run, we can begin diagnosing the issue. Is it a technical error that needs correction? Or perhaps they require more speed endurance work later in the training cycles? While the answer may be multifaceted, testing initiates the diagnostic process. I also record each repetition for every athlete in the 30m from a 3-point start, 30m fly, and the final stretch of the 20-second run, providing additional visual data to inform our direction.

So, is testing beneficial?

With more than a decade of "Testing Weeks" experience, I can confidently say that the answer is—it depends (haha). I believe it hinges on athlete and coach buy-in to the process and the objectives we aim to achieve through testing.

Speaking in broad terms, I categorize athletes based on their level of enthusiasm for testing:

The Testers: These athletes come well-prepared. They are the track enthusiasts who enjoy crunching the numbers as much as I do. They anticipate their stride analysis report immediately after the testing block. Testers want to have access to their complete testing history beforehand for comparison. Typically, they seek more than three attempts and welcome feedback between them.

The Tweeners: Tweeners arrive prepared, exert full effort, but display lesser interest in the results. They appreciate the reduced training volume during the recovery week and often ask, "Is that good?" after their attempt.

The In and Outs: These athletes warm up, complete the tests, and swiftly move on with their day. They usually give a strong initial effort but gradually lose enthusiasm throughout the reps. They show little interest in the results and may ask, "Are we done?"

Although I believe heavily in testing, a good friend of mine and former colleague & US High Jump Champion Jim Dilling often joked that "nothing correlates to anything." Simply put, an athlete could always give lackluster testing efforts, but "release the dogs" on meet day, completely skewing your initial projections.

That being said, I work to educate athletes on the importance of testing and what the group can gain from it collectively. Over the years, approximately 80% of the group typically buy-in, while the remaining 20% may not be as invested. I request good effort from all participants to ensure the most accurate data.

I don't believe it's necessary for the entire group to fall into "The Tester" category. I can confidently say that some of our program's finest athletes have fallen into the "In and Out" category, and this is not necessarily a detriment. In my experience, these athletes are often more seasoned and have achieved success at the national level. Their disinterest can often be attributed to their intense focus on competition. They have been following a successful plan at the required intensities each day, and, in some cases would rather spend recovery week dealing with the additional stresses of being student-athletes. While this may be situational, it's understandable that a fourth or fifth-year senior in their eighth or ninth testing week might appreciate some extra rest.

On the flip side, some argue that testing-type numbers can be obtained during daily practices, rendering dedicated testing weeks unnecessary. While we do time workouts, and our coaches can always utilize the timing system to measure segments, I have found that we garner greater buy-in and effort when gearing up for a testing week. Athletes welcome the break from regular training, and I gain data that helps shape our training direction as we move into the next block.

Naturally, meets serve as the ultimate test of training. However, I believe there is no harm in having qualitative benchmarks along the way. In reality, I would be wary of a training program that lacks tangible data to gauge progress. At a minimum, during most sprint sessions, we have a camera to record and provide visual feedback. I can easily use a timing app or count frames to ensure the desired intensity without always relying on my eye.

The replicability of your tests is paramount. As mentioned earlier, we consistently conduct tests indoors to eliminate weather-related variables such as wind and rain. The testing setup remains consistent each time to ensure accurate results. If you are unsure about how to set up a test, ask someone experienced to guarantee accuracy. My only reservation regarding testing arises when it is set up incorrectly. This can often lead to inflated testing marks, setting the athlete on a path toward future disappointments. Its easy to see when results are posted…if an athlete is said to be running 3.70 seconds in the 30m from a 3-point start with a Brower or Freelap timing system, while the TFRRS page shows a 10.70-second 100m PR—clearly the test is set up improperly.

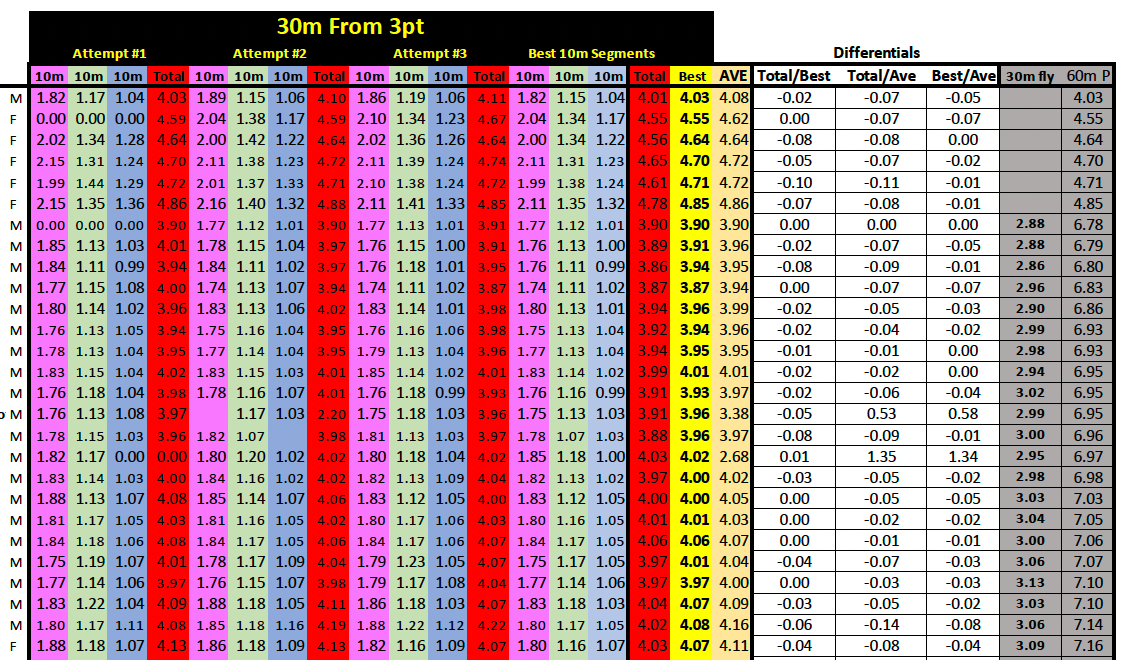

In conclusion, accurate, repeatable, and safe testing is essential. Always strive to educate athletes about the WHY behind testing. Their results not only inform future training blocks but also provide MEANING to their hard work. Below, I provide an example of the type of data we can extract:

The chart displays the final 30m from a 3-point start data from our week 4 testing. I was able to obtain 10m splits using our Brower gates. We averaged out the repetitions, conducted a "best segments" analysis, calculated differentials to assess the consistency of efforts, and, lastly, projected 60m times based on the speed testing.

So, if you ask me, there will always be a benefit to testing! You only know what you know, and testing will unlock unknown information!

P.S. I previously delivered a 90 minutes presentation on testing protocols at a state association clinic, which is available for purchase. If you're interested, please let me know!

Happy Coaching!!